Hello and welcome to another issue of the Weekly Vine.

This week, we take stock of Trump’s boring parade, explain why brown lives matter a little less, explore the fear illusion, remember David Beckham the footballer, and reflect on borders and immigration.

A Big, Beautiful, and Boring Parade

When I was an insouciant kid in boarding school, I was deemed Kachra Party (KP) and exiled to the rafters during annual parades (on Independence and Republic Day) for not being able to stay in line or flail my legs in unison like my peers. Unlike the other exiled community that shares the same initials, I had no qualms about said exile.

Now imagine my joy when, nearly two decades later, I saw an entire contingent march with the same disinterred gusto. One is, of course, referring to the semiquincentennial (how the hell does one pronounce that?) commemorations of the US Army, infamous for losing wars all over the world unless aided by the Red Army. Unfortunately, the anniversary coincided with chickenhawk President Donald Trump’s 79th birthday, so we got a snoozefest sponsored by Coinbase, Lockheed Martin, Palantir, and a bunch of other companies.

It was exactly as bad as one imagined, as the guests—much like yours truly during march pasts in boarding school—struggled to stay awake while soldiers and other members of the US Armed Forces marched with the enthusiasm of a snail returning home from a funeral on a lazy Sunday afternoon. The seats were empty because, unlike North Korea or Russia, America isn’t an actual dictatorship in the traditional sense.

The farce was reinforced by songs like Creedence Clearwater Revival’s Fortunate Son—a track that literally mocks chickenhawks like Trump who dodged the draft—playing in the background. All in all, it was the perfect metaphor for a democracy pretending to be an authoritarian state, led by a transactional tyrant whose morals are flexible and who seems intent on destroying the liberal world order that emerged after WWII.

Of course, much like Voltaire observed about the Holy Roman Empire, there was nothing particularly liberal or orderly about that world order—but that’s a debate for another time.

The Fear Illusion

The other day, a news anchor asked on social media: “What’s happening to couples in the Northeast?”—a pretty preposterous argument to float unless one can draw a causal link suggesting that marriages are somehow more likely to end in Macbeth-like fatal murders in a particular geographical location.

What it actually is, is a fine example of the Baader-Meinhof phenomenon, also known as the frequency illusion.

The term originates from a 1990s online discussion where someone mentioned they’d just heard of the Baader–Meinhof Group (a German far-left militant organisation), and then suddenly began seeing references to it everywhere. The name stuck as shorthand for this type of mental glitch—and it happens to all of us.

Take, for example, when you see a sign that says “Stalking not allowed” (quite common in the national capital, where men seem to need periodic reminders about consent). Suddenly, you start noticing similar signs everywhere. It feels like the universe is messing with you, but in reality, your brain is simply tuning into something it was previously ignoring.

Why it happens: The phenomenon is a combination of:

- Selective attention – Once your brain learns about something new, it subconsciously starts scanning for it.

- Confirmation bias – When you see it again, your brain takes note and thinks, “Aha! I was right—it is everywhere!”

Now, why am I telling you this? Because it’s the basis for so many of our modern anxieties.

Take the sudden barrage of news items about airplane snags after the horrific Air India crash in Ahmedabad. Suddenly, every TV channel and newspaper clipping seems to be about aviation issues—because editors and journalists aren’t immune to the frequency illusion either.

But is there any definitive proof that air travel is objectively less safe than it was a year ago? Not quite. It’s just that our brains are wired to worry. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t drag companies over the coals to ensure better quality control—but we should be diligent before jumping the gun and assuming systemic failure.

The odds of dying in a plane crash are about 1 in 8 million, whereas the odds of dying in a road accident in India are around 1 in 5,000—making road travel over 1,600 times deadlier than flying.

Maybe it’s your daily commute you should be afraid of.

Why Brown Lives Don’t Matter As Much

When a white police officer knelt on the neck of a Black man named George Floyd, leading to his death, it became a global movement that eventually sunk the Democratic Party. But for a time, Black Lives Matter was the most powerful social movement in the world—even the Indian cricket team, who might not be able to name a single victim of police brutality in India, took a knee in solidarity.

Now, when 42-year-old Gaurav Kundi, an Indian-origin father of two, died of catastrophic brain damage after allegedly being pinned down by police in Australia, there’s hardly a murmur—let alone a montage of global solidarity. Conflicting reports suggest he was intoxicated and arguing with his wife, which the police mistook for domestic violence. None of that changes the fact that a man lost his life following an altercation with law enforcement. And yet, the silence—even from the Indian press—is deafening.

Perhaps it’s because brown deaths don’t move moral compasses. Gaurav simply doesn’t evoke the same emotions as George. While that’s understandable on some levels—given America’s long and brutal history with race, and its compulsive need to overcorrect for its original sin—there’s a deeper reason: brown lives simply don’t offer the political payoff or financial traction required to fuel a global moral crusade.

It’s the same reason Western media outlets have no qualms referring to terrorists who murder Hindu pilgrims as “gunmen”, but would never dream of using such euphemisms if the same act occurred in Paris, London, or New York. Moral outrage, like everything else in this post-liberal order, is market-driven.

And Gaurav Kundi’s death, tragically, just doesn’t sell.

Sir David Beckham

“Beckham, into Sheringham… and Solskjaer has won it!”“Manchester United have reached the promised land.”

The corner came in like a hymn. Beckham’s delivery—whipped, precise, inevitable—was scripture in motion. In the annals of football, there are players who pass, players who dribble, players who score. But there was no one who could bend it like Beckham. Or to paraphrase Leonard Cohen: David had a secret chord that pleased the Lord.For United fans of the current vintage, it’s hard to forget how good Beckham and his mates were and how terrifying it was for opposing teams when they played together. Because at that moment we were all in a Gurinder Chadha film, hoping to bend it like Beckham and if we couldn’t copy his mohawk hairstyle, much to the chagrin of mothers and teachers.

You had Ryan Giggs running like a cocker spaniel chasing a silver piece of paper.

You had Roy Keane looking at you menacingly as he covered every blade of grass.

You had Paul Scholes hitting the ball with such power that it took Sir Alex Ferguson’s breath away.

And you had David Beckham pinging crosses and passes with such accuracy that it seemed barely human.

It’s easy to forget now, with the beard oils and whisky launches, the sarongs and showmanship, that before he became a brand, Beckham was a baller. And not just a decent one. A magnificent one. Read more.

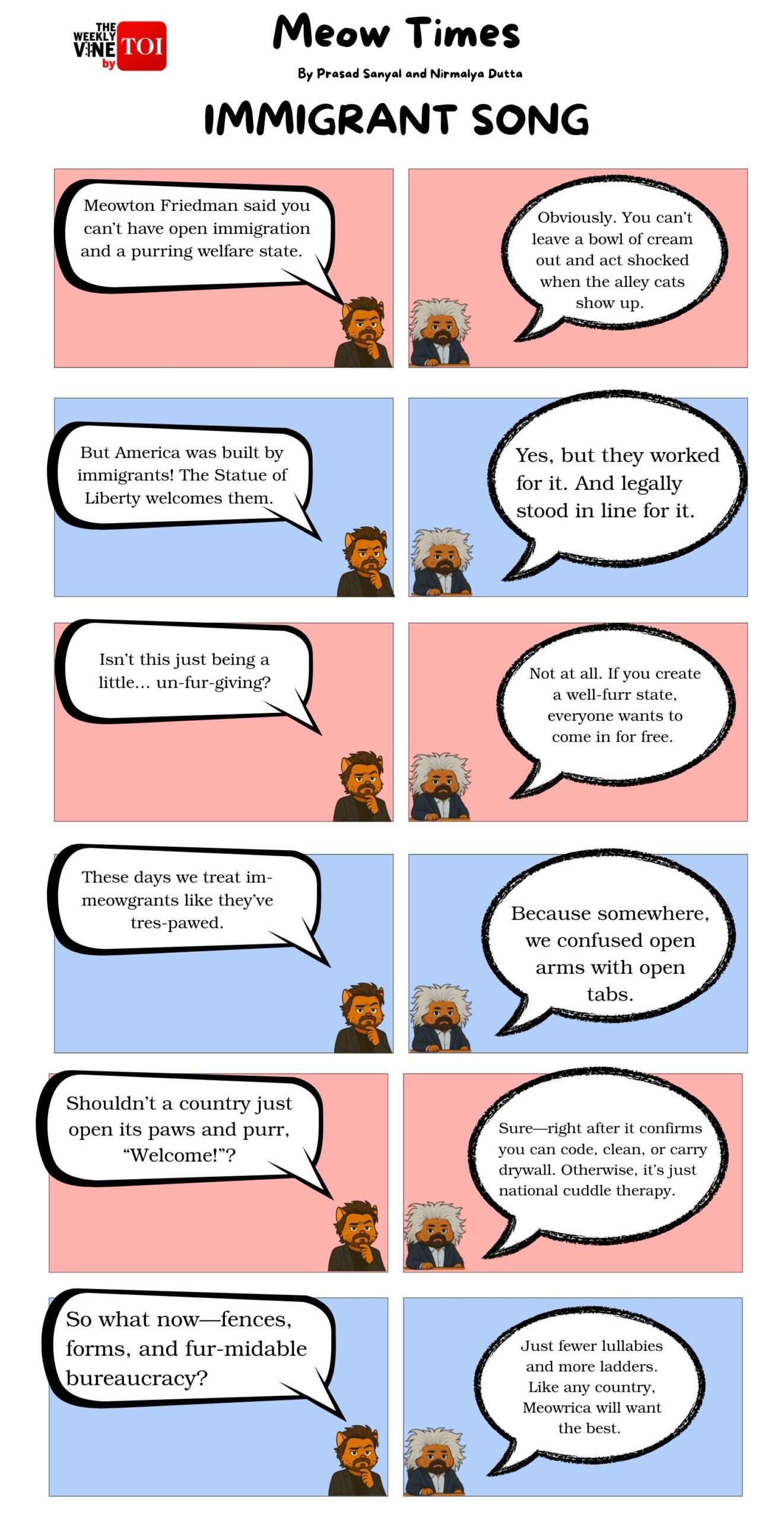

Post-Script by Prasad Sanyal: The Border Isn’t Where You Think It Is

There’s an old video of Milton Friedman doing the rounds on Instagram. Sepia-toned, clipped, and inconveniently intelligent, it shows the economist calmly explaining why immigration worked better before 1914—largely because there was no welfare system. Immigrants came to work, not to collect benefits. And in that measured, almost surgical voice, Friedman drops the line that still makes policy wonks twitch: “You can’t have free immigration and a welfare state.” Read more.

Disclaimer

Views expressed above are the author’s own.

END OF ARTICLE