We inhabit an age that mistrusts stillness. Movement is treated as virtue, speed as seriousness and fatigue as proof of commitment. If you are not visibly stretched, visibly overwhelmed and struggling to keep up, there is a quiet suspicion that you are not trying hard enough. The modern professional life resembles a perpetually overcrowded train in motion, in which everyone is standing, everyone is gripping something, everyone is being carried forward and very few remember where they boarded or where they intend to disembark, even as everyone remains determined to keep moving.

In such a climate, ‘what got you here won’t get you there’ acquires the status of philosophy. It flatters anxiety, dignifies restlessness, and tells you that your vague discomfort is not confusion but insight. It suggests that the unease you feel is evidence of growth, while quietly implying that ‘here’ is merely provisional, no more than a waiting room in which one is not meant to settle, a transit lounge designed only for passing through, a temporary halt before the real destination reveals itself somewhere further ahead.

But nobody ever quite defines ‘there’.

There is leadership, we are often told. There is scale, influence and impact. There is the next role, the larger team,, the heavier visiting card. There is always another platform to climb, another identity to assemble, another version of oneself to unveil and ‘there’ remains safely distant, just far enough to keep you walking.

Underlying all this is an unexamined faith in progress itself, a belief as old as modern civilisation and almost as fragile, which assumes that forward movement is necessarily improvement, that change is synonymous with advancement, and that what comes later must, by definition, be superior to what came before. Like the myth of civilisation itself, which promises that each generation stands taller than the last, the myth of progress reassures us that motion is meaning and novelty is virtue.

The genius of this system lies in the fact that it never permits arrival. The moment you reach somewhere, you are informed, gently but firmly, that you must outgrow it. Success now has a shelf life. Satisfaction is allowed only briefly, roughly for the duration of a congratulatory post, after which you are expected to resume your dissatisfaction.

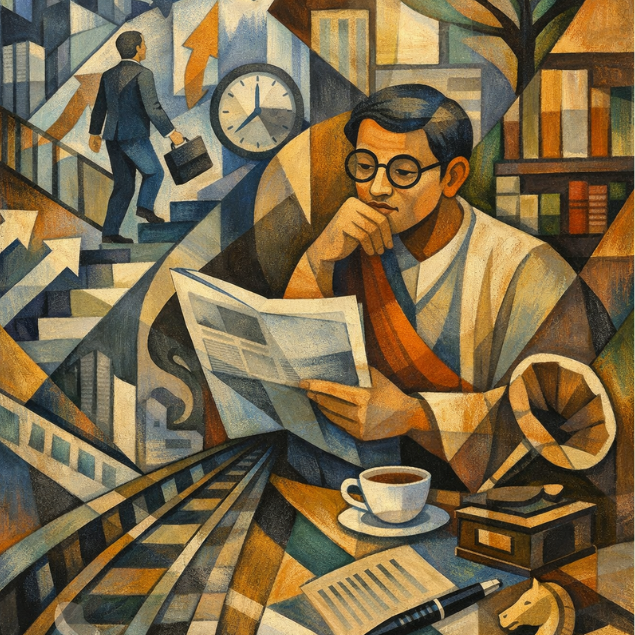

For someone shaped, however imperfectly, by the old Bengali bhadralok temperament, this permanent agitation is faintly bewildering. The bhadralok was not hostile to ambition. He valued education, competence, stability, and slow improvement. He believed in cultivating a profession, a reputation, and a life with some measure of continuity, and did not experience every decade as an opportunity for personal rebranding.

He read his newspapers and his books with care, debated endlessly with friends about poetry, politics, and the moral direction of the country, went to office without melodrama and returned home without complaint, and, without ever describing himself as being “on a journey,” managed to live a life that possessed rhythm, continuity, and quiet self-respect.

It was not a spectacular life, but it was coherent. Today, coherence, like dignity, rarely trends.

Every hobby must become a side hustle, every interest must become content, every pause must become strategy, until even rest requires justification, boredom must apologise, and silence must produce something. We have reached a point where even doing nothing requires a framework.

So when someone says, “What got you here won’t get you there,” what they often mean, without quite realising it, is that you are insufficiently unsettled, too composed, too steady, too un-panicked, which in an age addicted to urgency is faintly suspicious.

Older British humour understood this condition with remarkable clarity. In the 80s BBC series Yes Minister, progress is discussed endlessly, refined bureaucratically, and implemented cautiously, systems move slowly, people remain recognisably human, and nobody confuses velocity with virtue. Tea is served. Life continues.

And in the world of PG Woodhouse, the highest intelligence lies in knowing when not to take ambition too seriously, for his characters survive institutional absurdity not by hustling harder but by refusing to internalise its madness, and are therefore not lazy but psychologically self-preserving.

We, by contrast, have raised a generation that believes every life must resemble a presentation, complete with vision statements, milestones, and measurable growth while learning, maturity and wisdom quietly retreat in favour of charts and dashboards. Much of our compulsive motion, our fear of staying put for too long, is an attempt to outrun futures that exist largely in our imagination, much like Montaigne’s rueful admission that his life had been filled with terrible misfortunes, most of which never troubled him in the end, for we rush not because disaster is imminent but because it might be.

Of course, change matters as does learning and adaptation. No one is proposing stagnation, but growth is not always vertical. Some growth is inward, some is horizontal, and some is simply learning to practise one’s craft with greater patience and fewer illusions. Not every career requires a dramatic ascent, not every life needs a transformation montage and not everyone is meant to be permanently ‘on a journey’. Some people are meant to be reliable, competent, useful and quietly fulfilled, which in our times is considered dangerously modest.

The hustle narrative persuades us that unless we are racing ahead, we are falling behind, that unless we are constantly upgrading ourselves, we are becoming obsolete, and that staying put is evidence of fear. From a commercial point of view, it is a brilliant doctrine, for it sells urgency, mentorship, coaching, and permanent inadequacy, even as it rarely sells peace.

“What is wrong with going nowhere?” sounds almost subversive today.

Yet “nowhere” often means something quite precise: not chasing every trend, not auditioning for every reinvention, not living in permanent beta mode, but knowing one’s place in the world and finding it meaningful, choosing depth over noise, craft over spectacle, and continuity over chaos, and preferring steadiness in a culture addicted to acceleration.

Sometimes, yes, what got you here will not get you there. And sometimes it will. Sometimes experience is not baggage but ballast, sometimes consistency is not stagnation but reliability and sometimes staying is not fear but discernment.

The bhadralok instinctively understood this. One did not abandon a good life merely because it lacked glamour, nor leave a stable station merely because others were running, but cultivated dignity as a form of quiet resistance. So when asked where one wishes to go, the most honest, quietly rebellious answer may simply be that one is content to continue working, learning and living where one is, not for lack of ambition but from the conviction that a life does not have to be in perpetual motion to be meaningful.