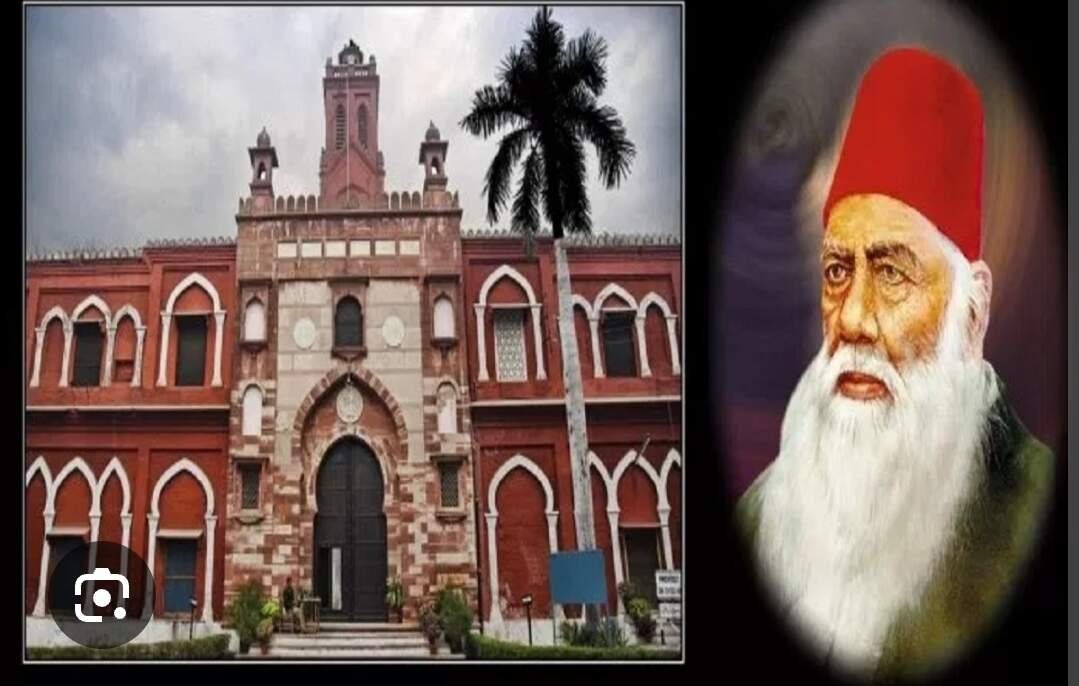

As the world, especially the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU) alumni community, celebrates Sir Syed Day (October 17), I remember the poet Allama Iqbal’s Uqaab or eagle. His Shaheen or falcon.

Eagle symbolises courage, strength, dignity, and self-respect. Though the literal meaning of Uqaab and Shaheen are different, Iqbal uses them interchangeably. For him, these birds are not mere avian creatures. They are sources of inspiration. He uses them to inspire mankind, especially youths. To aim high and strive to excel. Unlike the Kargas (vulture), Shaheen and Uqaab do not feed on the prey killed by others. They find their own prey and live off their own efforts. They are not parasites. They know how to find their own food, soar high and keep their dignity intact.

Contrasting the parwaz or flight of eagle and vulture, Iqbal says:

Parwaz hai dono ki usee aik fiza main

Kargas ka jahaan aur hai, Shaheen ka jaahan aur

(Both fly in the same sky, but the worlds of eagle and vulture are different).

So, why do I remember Iqbal’s eagle on the birthday of Sir Syed Ahmed Khan (1817-1898)?

Sir Syed could not have entered and remained eternally in our imagination had he not addressed the issues of his community through engagement with the youths. There are reformers and educationists. And then there is Sir Syed.

Sir Syed stands heads and shoulders above other reformists because he perfectly diagnosed the disease that paralyzed youths and also prescribed the panacea for it.

Sir Syed is a renaissance man because, as former PRO and director of Sir Syed Academy at AMU Dr Rahat Abrar says in an important book, he prevented India becoming Spain soon after the 1857 mutiny. For the world Muslims, Spain carries both fascinating and poignant history. But that requires a separate essay and let us leave that for another day.

Sir Syed would not have been remembered with so much love and respect from lakhs of Aligs (alumni of AMU) spread across the world, had he not engaged so intensely with the youths.

When he founded Madrassatul Uloom in 1875 in Aligarh, which became Mohammedan Anglo Oriental (MAO) College in 1877, metamorphosing into AMU in 1920, Sir Syed actually injected an antidote to atrophy, amnesia and apathy which afflicted the Muslim youths of the time.

Devastated by the British repression in the aftermath of the 1857 mutiny which Muslims had led from the front, the community had lost hope. Bereft of leadership and guidance, its youth sat idle. They didn’t see light at the end of the tunnel. It was Sir Syed who became the torch bearer.

Sir Syed who refused to work with the tottering Mughal Empire and preferred to earn his bread with honour and dignity as a servant of the British Raj envisioned the youth’s future. In modern education and scientific approach.

Sir Syed was not a poet. He did not have the beautiful words and mighty metaphors that Iqbal had. But he knew the power of the words. He was aware of human history which had witnessed cataclysmic times.

He employed words to convey his message.

So, before founding his college, Sir Syed founded Tahzibul Akhlaq, the Urdu magazine which became the powerful vehicle to infuse a new energy among the community which feared its own shadows. Through his perceptive essays in the pages of this magazine and essays by his many fellow travellers, Sir Syed reached out to the community. To stir it from its slumber.

In conference after conference, he spoke of a new horizon, a new dawn for “quam ke bachon”. Unlike Iqbal, Sir Syed did not address these youths as Shaneen’s children, but, like Iqbal, he wanted youths to become self-reliant. Agents of change.

The main purpose of establishing a residential institution (Aligarh was among the first educational institutions in the sub-continent to begin as a residential college) was to prepare a group of disciplined, educated youths who would be leaders. Not in the narrow sense of the term. But leaders in different walks of life. In politics, judiciary, bureaucracy, journalism…

Decades after Sir Syed’s death in 1898, it was noted Urdu satirist and humourist Prof. Rasheed Ahmed Siddiqui who distinguished himself with a delightful pastime. Whenever he came across a well-mannered, well-dressed stranger, Siddiqui would ask him whether he had ever been a student at AMU. It didn’t surprise Siddiqui if the stranger turned out to be an Alig and was so charming. It saddened Siddiqui if the refined stranger told him that he had been deprived of the boon of studying at AMU. That was the parameter perhaps Sir Syed too wanted students of AMU to live up to.

Iqbal, a great admirer of Sir Sayed, wanted Aligs to break the barriers and embody Shaheen and Uqaab.

Iqbal’s poem “Syed Ki Lauhe Turbat (Tombstone of Sir Syed)” is not just a tribute to Sir Syed; it is a clarion call to the youths too. It encapsulates Sir Syed’s reformist zeal and the poet’s passion. Iqbal says:

Banda-e-Momin Ka Dil Beem-o-Riya Se Paak Hai

Quwwat-e-Farman-Rawa Ke Samne Bebaak Hai

((The believer’s heart is clear of fear and hypocrisy

The believer’s heart is fearless against the ruler’s power).

There are many instances when students of AMU and Aligs elsewhere have shown this fearless heart. They have refused to succumb to pressure and refused to fall for inducement.

As the worldwide Alig community remembers their mohsin, their great benefactor, on his birthday with rousing speeches, eulogistic poetry, including invigorating, energetic recitations of Asrarul Haque Majaz-penned Tarana or the anthem, Yeh Mera Chaman Hai Mera Chaman…, they must remember their responsibilities too.

And one of the responsibilities is to rescue AMU from the depths of decay it has been pushed into. And I am not talking about just the physical decay. The decay and fractures are visible not just in the old, once beautiful heritage buildings built during Sir Syed’s time or within a few decades after his death. The decay is visible in the way the students on the campus are being prepared for the future.

One can cite innumerable areas begging for urgent attention. One of those areas is the Students’ Union. Initially called Siddon’s Club, the students’ Union Club at AMU has produced a galaxy of leaders in both pre and post-independence era. Since the administration does not want anyone to question its lethargy, its many undemocratic and unpopular decisions, it has kept the Students’ Union election in abeyance for months.

Let me cite a recent example of how the absence of Students’ Union encourages the administration to allow things and actions against AMU’s ethos and traditions. Former VC Dr Tariq Mansoor, now an MLC from the BJP, recently installed a dozen lights on the AMU campus. First of all, this was not needed. If he really wanted to use a portion of his MLC funds for AMU’s development, he should have used it to repair toilets at the many hostels. Or he should have put it to a better use like repairing the old and heritage structures on the campus.

His decision is baffling because, on the poles the lights were installed, also featured images of him and UP chief minister Yogi Adityanath. This was unheard of. This is a university campus and Mansoor, an alumnus, a former principal of its Medical College and its former VC, should have anticipated opposition to this illogical step. A report from the campus says that some students have removed those photographs from the poles. But when the motive is to earn admiration from your leader, such decisions are taken. Taken in haste with disastrous consequences. Had there been the Students’ Union, the likes of Mansoor would not have implemented their ill-conceived ideas so easily. Sensitivity of the student community must be kept in mind while introducing new policies or improving infrastructure.

I end this essay with yet another couplet of Iqbal where he uses eagle as a metaphor to enthuse and encourage youths. To aim high.

Uqaabi rooh jab bedar hoti hai jawanon mein

Nazar aati hai unko apni manzil aasmaanon mein

(When the soul of an eagle stirs among youths/

They see their goals in the skies).

Fly high, o farzandane Aligarh ( sons and daughters of AMU).